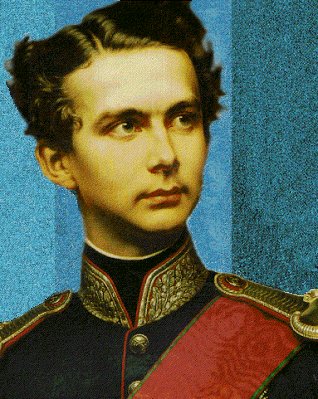

Admittedly this isn't the only period of German history I'm a fan of. For instance, the Hapsburgs! Crazy King Ludwig, Builder of Castles With Secret Opera Grottoes? Magic.

Look at the crazy eyes!

He's so pedestrian, though - everyone likes Ludwig, and so Nazis continue to hold a special place in my heart. This is a sentence I should probably not be typing, especially in Munich, the city where they began - still, at least a third of what I've read in the past year has been tangentially fascist-related.

While Germans and Iranian-Germans may not understand this eagerness to constantly poke the wound of the recent still-throbbing past, other expats do. In October, I walked into The Readery, Munich's jam-packed English-language bookstore, and said that I was looking for a book to take on a plane.

The bald, bespectacled, just-so store owner (who reminds me of Stanford from Sex and the City and whose name I never actually catch but who I have had numerous strange interactions with) nodded gravely at me. "Where are you going?"

"Istanbul," I said. (Did I mention that Nader and I went to Istanbul? And that I met his family? And that I bought a suitcase for ten dollars on a street corner at midnight, and that I got kicked out of a mosque for being American? No? Well...)

"Nice town," the bookseller said. "Well, what are you into?"

"Um, I've been loving ... memoirs, lately," I said. "You know, history." I was thinking of "Berlin at War: Life and Death in Hitler's Capital," the book I'd picked up and been unable to put down, even in crowded U-Bahns. "You know. Early twentieth-century stuff."

"In America?" he said, peering at me over his tiny round black glasses.

"Well, more Europe," I said. "Modernism. Um. Kind of. Or post."

"Oh, well then," he said, and led me to a shelf. As it turned out, he knew exactly what I wanted without me even having to ask for it. At no time did I say "I want to read about Nazis," but I went home with an armful of tangentially-related literature.

My favorite of the books - which I would wholeheartedly recommend that the entire world read - turned out to be Diane Ackerman's "The Zookeeper's Wife", a rambling, fascinating, unclassifiable book about, among other subjects, little-known Nazi mysticism; their attempts to back-breed animals and repopulate German forests with proto-Teutonic relics of the past; and a Polish couple in Warsaw who rescued three hundred Jews by hiding them partially in animal cages. I lent it to my mother when I went home for Christmas - she read it eagerly, as it's proof that Polish people can be major badasses.

Speaking of family, the little man from the Readery also sold me Jonathan Guinness' "The House of Mitford". This book turned out to be an incredibly cost-efficient purchase, as four months later I am still reading it. I did not end up taking it on my plane to Istanbul, because it is a neat six hundred pages and because the first two hundred of those are all about the dry nineteenth-century activities of various wealthy old men. I have, however, gotten over that hump, and now I'm reading about the children of Lord and Lady Redesdale, all seven of whom (six girls, one boy) grew up to become enormously influential (famous hostesses, authors, Communists, etc) and hung out with anyone who was anyone in Britain in the early 1900s.

Maybe the most famous Mitford is Nancy, who wrote still-readable novels, but the most notorious Mitford is Unity, her sister, the one in the middle there with the long scary Mormon braids. She was a twenty-year-old exchange student in Munich in 1938, and one of her favorite activities was to leave her apartment to go hang out at the Osteria Bavaria.

The Osteria wasn't destroyed in World War II, unlike much of Munich; it's even still a restaurant, and still named the Osteria. Quite oddly, it's near the University, on Schellingstrasse, not two blocks from where I bought the book about the Mitfords.

It was, and remains, sort of a boring mid-level Italian place, a German Olive Garden. It would have no notoriety at all, were it not for the fact that it was Hitler's favorite restaurant.

Om-nom-nominous.

Unity would sit near the front of the place all afternoon, stirring a coffee and waiting for a glimpse. A few times a week, Hitler would roll up (at weird times, usually mid-afternoon) for lunch (vegetarian, no alcohol) and then spend several hours surrounded by various hangers-on (Goebbels, Wagner, etc) at a round table in the back. On days when this happened, Unity and the occasional friend would dither at her table in the front, too excited to eat, rather the way I might behave if say Keanu Reeves were munching salad right behind me.

Megalomaniac or not, Hitler was bound to notice the really quivery woman sitting at the front of the restaurant sooner or later. Unity got lucky: she was young and made-up and blonde, and Hitler was already going insane from syphilis and rather enjoyed being stalked. He didn't have the SS arrest her. Rather, he had the maitre'd go over and invite her for dinner. (Goebbels had allegedly been too nervous to do it.)

He'd had no idea who she was - no idea that she was English, and utterly no idea that her family was friends with Churchill. But once he found out, and once he realized how hilarious her weird Englishy German was, they were inseparable. Not in a sexy way, Jonathan Guinness insists. (Although, on a side note, did you know that before Hitler took women to bed, his version of foreplay was showing them how long he could hold his hand in a salute?)

Rather, Unity just came and oh, spoke at Nurnberg in front of thousands of people about her "wishes that Naziism would spread to England". She wrote a crazy letter to a German tabloid explaining how 'sneaky' the English Jews were, 'not like the Jews in Germany, who are much more obvious about their subversive activities'. She would wear her Nazi badge everywhere, even Prague, which was at that point preparing to be invaded by the Germans and understandably more than a little bit hostile to Hitler's blond friend showing up all swastikaed. It was love.

Until Unity started figuring out that things weren't going to be all fun and Wagner concerts forever.

All of her English friends started leaving the city. And Hitler started saying things like, "Well, Germany WANTS to be friends with England, but friendship cannot be one-sided - it must be RETURNED!" And then he went and Anschlussed Austria, and took the Suedetenland, and moved in on the Czechs, and invaded Poland - and pretty soon Unity couldn't quite mesh being English with being German, because now England had declared war on her adopted country.

I assume this was it. I mean, she was also nuts. But I think that's why, in August of 1940, she took a cute little lady handgun into the English Gardens (where? probably downtown, near Odeonsplatz) and, as soon as she thought nobody was watching, shot herself in the forehead.

That's the part of Unity's story that really gets me. She can have coffee with Hitler near the university we both studied at all she wants; she can go shopping in an older version of Marienplatz and drink beers in the Hofbräuhaus, sure; but when she shoots herself in MY English Gardens, well, then I've got to reconcile her somehow with myself and the place where I go to swim in a river and kiss my boyfriend.

That's the choice we're faced with, though, isn't it? Reconcile it, or ignore it. It's impossible to just let history be, especially when it comes up in unexpected places to strike, like a snake in the grass.

Last weekend, I was out near Sendlinger Tor, ready to head over to a friend's house, when she called. "Don't come," she said. "There's a neonazi rally."

"What the hell?" I said. "I'm almost there," and I could hear it - here I was walking down the street in my rain boots, glasses foggy, and there it was, the distant barking in a bullhorn. Nazis, shouting, real ones.

In the drizzle, I walked underneath the Sendlinger Tor (that place of bars and pizza joints and a Christmas market) and crossed the cobblestoned street - there, blocked off by forty police cars, was the Sonnenstrasse; and there were the Nazis.

In real life, it turns out that Nazis, or at least Nazis who march, are mostly pale young men. Many of them have shaven heads, it's true, but more of them have beards - big, bristly, girl-defying ones, or little painstakingly shaven ones dyed into points. All of them wear black - no exceptions, no splashes of color - and mostly that black is leather jackets or sweatshirts.

They may sound intimidating, but the fact is, most of them seemed to be hiding. True, it was raining, but not that much - nobody's sweatshirt needed to be pulled up to completely hide his face, as theirs were. And they were carrying banners, yes (no actual slogans - just an abbreviation), but they clutched them as if they were security blankets.

Contributing most to the impression that they needed protection were the hundreds of policemen surrounding them, policemen, bored and confused, in full-on riot gear and shields, facing outward around a Nazi knot. The shields were necessary: surrounding all of it, the outer ring of a tree, the rim of a target, were the counter-protesters, people who far outnumbered the Nazis or the policemen.

People who were angry. People who took up chants like "Wir wollen keine Nazi schweine", and shouted boos when the man with the loudspeaker started to bark about Auslaender taking young Germans' jobs.

"As an American," I shouted at them in English, "I'm offended. Deeply." I called Nader, who was at home, and who (loving a good protest) was deeply disappointed that he wasn't also there. "Yell at them hard for me, honey!" he said.

So I chanted with the crowd. I tried to yell some things of my own, but protesting in a foreign language is hard, and I had to admit, other people were doing a fabulous job of yelling things which seemed to make the Nazis go red in the face already. The Germans were there, and they were pissed that someone was seriously trying to do a Neo-Nazi march in the middle of Munich. Disgruntled older couples holding shopping bags were bawling at them; single men, couples, hangers-on, a group of cute young hippie teenagers and a gang of kids in sweatshirts that said something like Israeli Liberation - everyone was angry, and the Nazis just looked sheepish.

I hung around for awhile, but it seemed nothing was really being done or happening. So then I headed home, rain boots squeaking and chants echoing against my back. At the end of the day, apparently, I remain an American, and an observer; here in Munich, I'm surrounded by history that is not mine, and the best thing I can do is look sternly at it.